In 1954, Che Guevara, as part of a geopolitical analysis that was sound in most ways, speculated that if all of Latin America was lost to the US Empire, the “abrupt loss” of cheap resources would hurt US industry so much that Washington would rally the entire working class (with the exception of African Americans) behind the “totalitarian measures taken towards maintaining Latin America in a colonial state”.

If a majority of the US public rejects a war, or supports health care being free at the point of use, or thinks trade unions should be stronger - that doesn’t mean it gets what it wants. But Che didn’t mean that the US government would disregard public opposition. He meant that opposition would be negligible - except in the African American community which was only about 10% of the population at the time.

With several decades of hindsight we can see that Che’s speculation on this point over-estimated how closely US imperialism aligned with the interests of the US working class. Che had not yet seen the US sacrifice tens of thousands of its own troops in a failed effort to re-colonize Vietnam, or deal with the upheaval resulting from that war in the US public, or ever witness the US dramatically rolling back concessions to its the working class due to the strain of maintaining an empire, or witness the several decades the US spent failing to re-colonize Cuba.

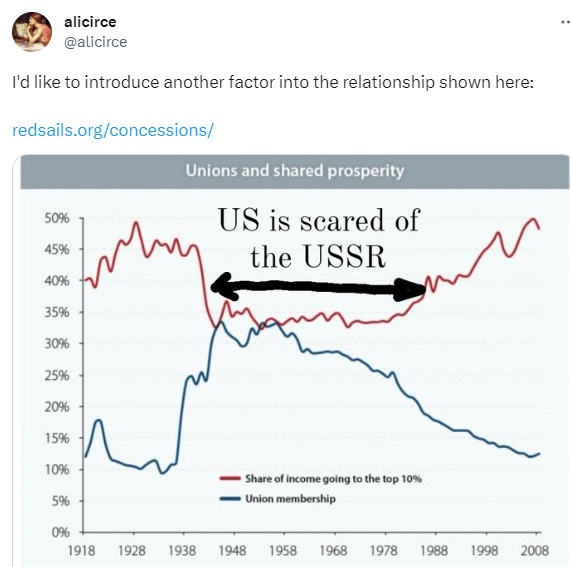

Che’s speculation looked much more convincing in 1954 because the US was in the midst of delivering big concessions to its working class. Alice Malone has an excellent piece up at RedSails.org showing that concessions to the US workers were driven by fear of the Soviet Union. Of course the concessions were also mixed with brickbats against communists, civil rights activists, anti-war activists and vulnerable communities at home. But the large scale of the concessions was undeniable.

However, the costs of those concessions became very alarming to the US government by 1971 (a key year as we’ll see) in two ways: ideologically and economically.

The ideological cost of concessions

I wrote recently about the memo US Supreme Court justice Lewis Powell wrote to the US Chamber of Commerce in 1971. He was dismayed by what he regarded as alarming independence of US academia, media and politics from corporate power. The crackdown Powell wanted could only be achieved by reversing the gains that the working class had achieved in security and dignity. Under capitalism, concessions to workers are like medicine. Too high a dose threatens capitalism’s survival instead of curing its political instability. Concessions can give working class people the free time, access to higher education and the confidence to question “the enterprise system” as Powell called it.

Che wrote in 1954 that it would be “useless” to “demand that the working class of the North look past its own nose” because the propaganda system was too strong (“the press totally in the hands of big capital”) and union representatives often playing a reactionary role. But only sixteen years later, the likes of Powell wanted the concessions rolled back precisely because much of the public was gaining the confidence to “look beyond its own nose”.

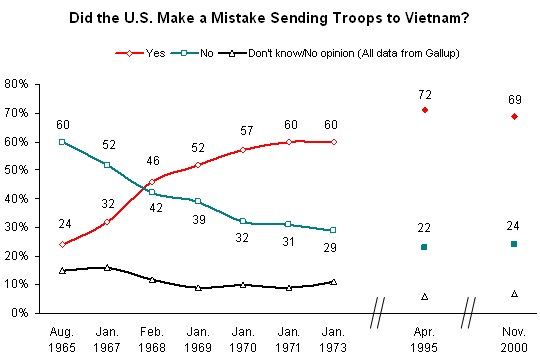

As early as 1965, opposition to the Vietnam war was already significant (25%). African Americans at that time were only 10% of the population, so the opposition already extended far beyond that community. By 1969, a majority of the US public was opposed.

1971 was the year that the Pentagon Papers was published thanks to Daniel Ellberg’s rebellion against a system that had given him a well paying job as a military analyst. It was also the year that a group of white professional class activists broke into an FBI office and stole documents that ended up exposing the COINTELPRO program. It had been operating since 1956 and viciously targeted a broad range of leftist groups in the US, and aimed to keep some elements of the far right, like the Ku Klux Klan, under control.

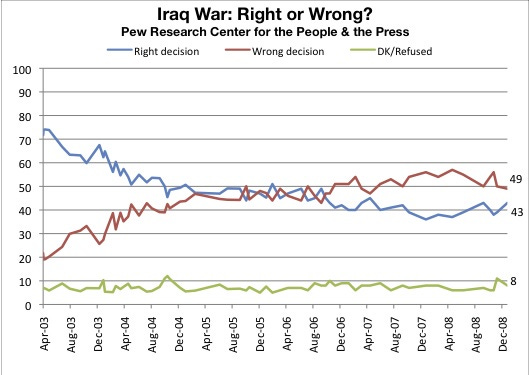

US fatalities in Vietnam were miniscule compared to what was inflicted on the Vietnamese: 58,000 versus 3 million respectively. But the US never again tried to convince the public to accept anything close to that level of death (only about 3% of its active force at the time) among its own soldiers. That is simply beyond the capacity of the propaganda system. Nixon abolished the military draft to weaken anti-war sentiment among the “middle class”. Yet even with the much lower fatality rate of the US war in Iraq (4487 troops over an eight year period) public support dropped below 50% within two years.

How can a “volunteer” military, one that is expected to actually fight to maintain the empire, be sustained in an overly affluent society? That’s one of the factors that make it difficult for the US to offer the more generous concessions that its imperial accomplices like Sweden offer to its people. Michael Parenti pointed out that in the mid 1970s top business leaders were dismayed that “the masses” want “big government” to deliver the kind of social democracy that exists in Sweden and Denmark. Why couldn’t the most powerful country in the world simply match or surpass what the Scandinavians did? The reason is that leading an empire imposes extra costs.

Dismantling Bretton Woods, financializing

1971 was the year that US President Richard Nixon stopped the US from exchanging dollars for gold at a fixed rate. In other words, Nixon dismantled the Bretton Woods system that the US itself had imposed on the world after WWII.

Economist Daniel Fusfeld identified the Vietnam war as the main driver of a balance of payments crisis that forced Nixon’s hand by 1971. Economist Michael Hudson similarly summed up the problem: “every single year its [the US] balance of payments moved into chronic deficit that got deeper and deeper until 1971 when it was forced off gold. The entire balance of payments deficit was equal to, year after year, to America’s military spending abroad” [1]

Under Bretton Woods, the US had decades of rapid productivity growth that was able to pass along as concessions to its working class while also fighting wars in Korea and Vietnam and maintaining hundreds of foreign military bases. But by 1971, doing all those things at once led to a run on the dollar. The US stock of gold fell to below $10 billion in 1971. It had been $26 billion in 1949. Big adjustments had to be made

Michael Hudson and Radhika Desai explained that Nixon’s decision in 1971 forced the US to “deindustrialize”. It initiated a transfer of wealth to the financial sector since it then had to increasingly attract speculators to keep the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency. As Desai put it, Nixon’s decision marked a shift from a “productively-oriented financial system” to a “speculatively-oriented financial system” that “strangles” industry. Industrialists initially objected but they often responded by shifting into the financial industry.[2]

US economist Dean Baker noted that “The broad finance, insurance, and real estate sector has more than doubled as a share of GDP over the last half-century, increasing from 5.5 percent of GDP in 1971 to 12.0 percent in 2021”

A separate analysis by Baker shows that productivity growth in the US was 3.05% in the 1948-1973 compared to only 1.19% in the 1973-2006 period. [3]

As the Reagan era began in 1980, post-war concessions to workers were rolled back even further and faster. As shown in the chart below (taken from Baker’s analysis) not only did productivity growth slow, but median compensation no longer kept up with the slower productivity growth.

Who really benefits from the Empire?

One reasonable answer to this question is nobody - nobody with a remotely civilized worldview that is. Nobody who values survival over the power lust of the few can be said to benefit overall. The Empire literally threatens to kill us all through nuclear war and climate collapse.

Also consider two “luxuries” that US citizens are told they can’t afford: free (at the poit of use) university education and health care. Cuba has both. No empire required. Cuba has, for twenty years, maintained a lower child mortality rate than the US. That doesn't mean life is easy in Cuba. Six decades of Washington’s economic warfare on Cuba have taken a toll, but so have forty years of neoliberalism inside the US.

According to a poll done last year by Pew “60% of Black Americans say their household finances meet basic needs with at least a little left over for extras, compared with 71% of all Americans”. In the narrowest terms, capitalism can’t deliver basic dignity and security to at least a third of its own people in the imperial core.

It should be a far less daunting task to rally working people in the US against imperialism than it appeared to Che in 1954.

NOTES:

[1] I did a Twitter thread three years ago citing excerpts from Fusfeld’s economics textbook. Nixon’s retreat from the Bretton Woods system is also discussed by Hudson and Desai here and here .

[2] Hudson remarked “a company like GM today is probably going to make more money by lending you money to buy their cars, rather than by making their cars”.

[3] These numbers and the chart below use Baker’s adjustment to productivity data for “usaable productivity” that actually goes directly towards raising incomes