STUDYING DAS KAPITAL: Part 1 (of 8)

Summarizing , mostly defending and, at times, critiquing Volume 1

INTRODUCTION

These are discussion notes for every chapter of Das Kapital Volume 1. Marx’s analysis of capitalism was quite brilliant, though it had some flaws. In eight different articles I will summarize, mostly defend, and at times critique, every chapter. There are no references to Hegel or “dialectical materialism” in these notes. Such references are actually very rare in Das Kapital. But despite having no interest in the metaphysical aspects of Marx’s thought (or anyone else’s) I consider myself a Marxist. If the metaphysics is important to you, the Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL) offers an online course on Volume 1 that references Marx’s metaphysics.

Marx divided Volume 1 into eight parts. This article goes over Part 1. Links to articles that study the other parts will be placed here as I complete them: Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7 and Part 8. If you prefer to download a PDF with all eight parts of my study notes combined into a single document, click the button below to do that.

CHAPTER 1: Commodities

Das Kapital (Volume 1) as a guided tour through Hell.

Marx began Das Kapital with a very theoretical chapter exploring the nature of a commodity. It is easy to imagine editors begging him to start with chapter 10, where he launches an attack on capitalists that trembles with indignation. Why open with a dry theoretical chapter? Why not open with fireworks to get the reader’s attention - to explain why it’s worth soldiering through the theoretical discussions that make up about 60% of the book?

It seems the answer lies in the way Marx decided to structure the book.

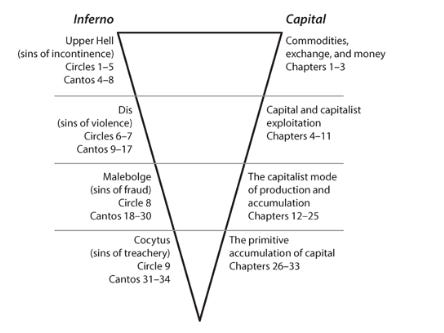

William Roberts argued persuasively in his book “Marx’s Inferno” that Karl Marx structured Das Kapital Volume 1 to parallel Dante’s Inferno. Look over the diagram below which is taken from Robert’s book.

In Dante’s Inferno the reader is taken through a guided tour of the different levels of Hell. Marx takes us through Capitalism’s Hell on earth (mainly focussed on England, the most advanced capitalist country of his time). In many chapters (which Robert’s notes make up to 40% of Volume 1), Marx is simply guiding us through history, often diving into detailed government reports about working conditions in England. It’s grim reading, much like a guided tour through a human-made Hell.

But the opening three chapters of Das Kapital are a tour of Capitalism’s Upper Hell - where the sinners are punished for sins that are less severe and deliberate than the ones for which they are punished in Lower Hell. In Upper Hell they are punished for “sins of incontinence” - stemming from lack of discipline and control.

So the opening chapters discuss the lesser sins of capitalism, and aim to lay the theoretical foundation for understanding it. Hence, the theory-heavy opening chapters that don’t passionately attack capitalism.

Use-Value versus Exchange Value

In Chapter 1, Marx explains the difference between a use-value and an exchange value of a commodity. This is not original to Marx. For example, Adam Smith (whom Marx cites very often in Das Kapital) also noted that distinction. But Marx made that distinction the foundation to his analysis of capitalism. As becomes clear in later chapters, you can not overstate the importance of this concept to Marx's analysis of capitalism.

The concept is very simple. For example, the use-value of water is practically infinite. We can’t survive more than three days without it. But a typical water bill in Ontario is presently only $90 per month. What we have to give up (i.e. exchange) to get a commodity is what Marx defined as its exchange value.

Note that when Marx refers to “value” without any qualifier in Das Kapital, he means exchange-value. For example, he says in Chapter 1 that “A thing can be a use value, without having value.”

Things can have use-values that are not commodities. Marx gave the example of air. Another example he gave is food people grow to feed their own families, and that is not exchanged with their society for other things. To have exchange-value a thing has to be exchanged.

But Marx also says in this chapter that he does not consider it an example of commodity exchange when serfs paid rent to a feudal lord using the corn they grew on the lord’s property. As William Roberts put it “Marx is committed to the claim that the products of human labor did not have [exchange] values in ancient Athens, or in Carolingian Europe, or under the Gupta dynasty”

Why? This reason is that to Marx when commodity exchange happens when the items are produced for anyone who can buy them, for society as a whole:

Whoever directly satisfies his wants with the produce of his own labour, creates, indeed, use values, but not commodities. In order to produce the latter, he must not only produce use values, but use values for others, social use values. (And not only for others, without more. The mediaeval peasant produced quit-rent-corn for his feudal lord and tithe-corn for his parson. But neither the quit-rent- corn nor the tithe-corn became commodities by reason of the fact that they had been produced for others…

It is also worth stressing that Marx envisions commodity exchange as taking place only when there are a wide array of commodities available to society. Recall the opening words of Das Kapital:

The wealth of those societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevails, presents itself as "an immense accumulation of commodities," [emphasis added] its unit being a single commodity.

Later in the book Marx explores the conditions required for widespread commodity exchange to take place as capitalism develops but does not yet prevail in a society.

The Labour Theory of Value (LTV)

Marx introduces the LTV in this chapter: “If then we leave out of consideration the use value of commodities, they have only one common property left, that of being products of labour”.

The LTV is one of the favourite punching bags of anti-Marxists. Some dismissals of the LTV have even been largely accepted by some Marxists. This can make people reflexively dismissive of Das Kapital and even discourage them from reading it. Why read such a long and difficult book if one of its key theoretical claims has been thoroughly refuted? Well, for starters, because the LTV hasn’t been refuted. It stands up. Before getting into debate about the LTV that has spanned well over a century since Marx first wrote about it, let’s review what Marx said about it in chapter 1.

Marx says the quantity of labour time required to make a commodity determines its exchange value. But he cautioned that exchange value is not increased by working very slowly, inefficiently or incompetently. Exchange value of a commodity is determined by “The labour time socially necessary … to produce an article under the normal conditions of production, and with the average degree of skill and intensity prevalent at the time”.

What if workers become more productive because the tools (including machines which can be thought of as very advanced tools) become better as a society’s knowledge base expands? Would that not drive down the labour time required for each commodity produced- therefore drive down the exchange value per unit? Yes, that is exactly what Marx says in this chapter.

Objections to the LTV

What about demand? This is a question that might come up if you’ve studied some economics before reading chapter 1. It is not addressed by Marx in the chapter, but can’t it be objected that society's tastes determine value? What if everyone suddenly hated the violin and loved guitars? Yes, that would drive down the exchange value of violins to zero because society would deploy zero labour time to making violins. Also, while tastes determine what particular food we like, or music we listen to, or clothes we wear, tastes do not determine our need to eat, cloth ourselves, or amuse ourselves. Tastes do not determine the raw materials, machines and skills required to make things. Whether you want guitars or violins you’ll need wood to make them and steel to make the tools that make them. Labour time will be deployed to get the wood and steel, and then to transform those raw materials into guitars (or violins). Changes in demand do not impact Marx’s assertion that the ultimate measure of exchange value is labour time.

What about energy? What about land? What about capital? Labour is not the only input to the production of commodities. That would be only true in a “simple and rude state” that Adam Smith talked about (where humans only hunted deer or caught fish) and nobody lent money or charged anyone rent. This was the line of attack economists like Paul Samuelson made on the LTV.

Marx’s most ambitious effort to defend the LTV was made in Volume III of Das Kapital. It was published posthumously. Only Volume I of Das Kapital was published while Marx was still alive. Marx attempted to show mathematically that prices in a capitalist economy are proportional to labour time. If the LTV holds up that is the least you should be able to do. If labour time is the ultimate measure of exchange value, then prices should be proportional to all the direct and indirect labour time required to make commodities.

Marx‘s approach to proving this in Volume III was flawed (Ian Wright showed) because it failed to consider the labour time required to produce the goods and services consumed by capitalists. A similar consideration applies to land owners. Rent and profit income ultimately consists of goods and services produced by workers. So by adopting a broader definition of labour costs than Marx did, Ian Wright showed that prices are proportional to labour time.

But Wright cautioned that you could also show that prices are proportional to energy or other basic inputs like water. So isn't it arbitrary to assert as Marx did that labour time is the ultimate measure of exchange value?

No. Water and energy did not design economic systems, and our goal is presumably not to ensure that water or energy are happy. If humans designed an economic system for human goals then it is quite rational to center human labour in a theory of value. Moreover, other basic inputs do not innovate during the production process. Humans do. But that’s enough jumping ahead for now. Let’s get on with the rest of Chapter 1.

Skilled vs unskilled labour.

Marx begins section 2 of the chapter as if answering people who might challenge the LTV by asking “but what about skilled labour?” “What about the fact that labour of various types of various levels of skill exists?”. All the different types of skilled labor, Marx says, are varying multiples of the base unit of value: the “simple unskilled labour” which “exists in the organism of every ordinary individual.” Hence “For simplicity's sake we shall henceforth account every kind of labour to be unskilled, simple labour”. And indeed, applying the LTV, it takes more labour time to produce skilled labour due to the training and regulation requirements. [Marxist scholar Ian Wright has criticisms of how Marx delt with simple and complex labour in Volume 1. I hope to wrte a piece about Wright’s critique in the future]

Marx goes on to observe that since any commodity’s exchange value is equal to the quantity of labour time “embodied” in it (that means all the direct and indirect labour time required to make it) then it is always possible to express its exchange value as some multiple of another commodity’s exchange value.

Another observation he makes is that a society may increase the total use-value of the commodities it produces while at the same time reducing the total exchange value of those commodities. This is possible if productivity changes sufficiently shorten the total labour time required to make the commodities. Imagine a society where everyone works 6 hours a day but produces more of what it did when everyone works eight hours per day. Jumping ahead in the book again, Marx will explain why this happy outcome does not occur in capitalism despite its relentless drive to increase productivity.

Total exchange value is constant if total hours worked is constant? No

Marx also says that “However then productive power may vary, the same labour, exercised during equal periods of time, always yields equal amounts of [exchange] value. But it will yield, during equal periods of time, different quantities of values in use.

Imagine an economy becomes more productive and therefore produces more commodities but keeps the total number of hours worked the same (and the same number of workers). Marx says that in this case the workers add the same amount of new exchange value. In Chapter 8 this will be clarified to distinguish between the new exchange value (labour time) added by workers on the job in the present, and the old exchange value (labour time) that is “transferred and preserved” in the raw materials they use. Total exchange value consists of both new and old exchange value (direct and indirect labour).

The Form of Value or Exchange-Value

Once you have a society where “free” workers produce a large number of commodities that are exchanged, the limitations of expressing their exchange values relative to each other becomes readily apparent. If “ the equation, 20 yards of linen = 1 coat, becomes 20 yards of linen = 2 coats, either, because the value of the linen has doubled, or because the value of the coat has fallen by one-half”. The true measure of exchange value is the necessary labour for its production. Marx says he believes that Aristotle fell short of developing a labour theory of value because he lived in a slave society where it could not be conceived that “all kinds of labour are equal and equivalent” because the very notion of human equality had not yet “acquired the fixity of a popular prejudice”.

Another problem with expressing the exchange value of commodities relative to each other is possibly comparing the use-value of one with the exchange values of others.

When a large number of commodities is being produced and exchanged there is inevitably a drive to find a “universal” equivalent with which to quantify their exchange value. Inevitably that universal equivalent becomes money.

Commodity Fetishism

The last section of Chapter one is titled “The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret Thereof”. Marx says relations between all the workers in an economy appear to them as if they were social relations between the commodities they produce. The nature of the economy is obscured to everyone, including the capitalist, especially when markets are very competitive. The commodities seem to have properties that drive capitalism, rather than capitalism being a human-run process. Marx’ sarcastic quip nicely drives the point home “ so far no chemist has ever discovered exchange value either in a pearl or a diamond.”

This idea that commodities rather than people are steering capitalism’s ship relates back to “sins of incontinence” Roberts talked about: since they stem from lack of discipline and control. People resign themselves to exploiting (and being exploited) and to enduring crises within a system they don’t understand and cannot control as isolated individuals.

Adam Smith famously put a very positive spin on the way collective decisions are made in capitalism through countless small individualistic, myopic decisions: his “invisible hand”.

A casually racist remark is made:

For an example of labour in common or directly associated labour, we have no occasion to go back to that spontaneously developed form which we find on the threshold of the history of all civilised races.

These kinds of comments are very rare in Das Kapital but I feel I should point them out.

CHAPTER 2: Exchange

This chapter is a preliminary brief discussion of money before he explores (in the next chapter) how it functions under capitalism. .

Before capitalism, Marx says, it was nomadic peoples who first developed money. They moved around so much that they constantly needed to carry out trade with foreigners. He notes that slaves were used as money, and that it was during the “French bourgeoisie revolution” that land was, for the first time, used as a basis for money. He said that it required an advanced bourgeois economy to try that.

He ends by setting up his challenge for the next chapter:

In the last decades of the 1 7th century it had already been shown that money is a commodity, but this step marks only the infancy of the analysis. The difficulty lies, not in comprehending that money is a commodity, but in discovering how, why, and by what means a commodity becomes money.

In the footnotes, anticipating the argument he develops in the next chapter, he says that if we try to abolish money while retaining commodity production “We might just as well try to retain Catholicism without the Pope”. The capitalist features of “commodity production” are fleshed out in future chapters.

CHAPTER 3: Money, Or the Circulation of Commodities

Money is not really what makes it possible to compare the exchange value of different commodities. The exchange value of all commodities is the direct and indirect labor time required to make them. That’s what makes exchange values comparable, and therefore why money can be used for that purpose. A “price” is a “money form” of a commodity’s exchange value.

Money itself (gold coin in Marx’s day) can rise or fall in its exchange value like any other commodity. Marx mentions the following possibilities.

1) Exchange values (direct and indirect labour time) for all other commodities except money remain constant. In this case Marx says a rise or fall in the exchange value of money causes no change in relative prices. Only nominal prices change. Suppose a week’s supply of bread costs 1 oz of gold in year 1, but goes up to 2 oz of gold in year 2. If the price of every other commodity also doubled in year 2 then relative to each other the other prices haven’t changed.

ASIDE: This case Marx mentions is quite hypothetical because if significant money lending takes place in an economy then inflation would end up impacting relative prices. Inflation would transfer wealth from lenders to borrowers. If I borrow 1 oz at 10% annual interest then my interest charges are 0.1oz- equal to 1/10 a week’s supply of bread if there is no inflation, but only equal to 1/20 a week’s supply of bread if inflation doubles nominal prices when my interest payments are due.

Less expensive borrowing could lead some manufacturers to more heavily invest in machines that increase productivity thereby lowering prices. Unless that happens for all manufacturers to the same extent then there would be changes in some relative prices.

Of course I don’t mean to say that inflation harms only money lenders. Depending on the level of inflation (and on which prices are increasing relative to others) it can also harm most people.

2) There is a rise or fall in the exchange value of money but, at the same time, the exchange value of other commodities is falling, rising or staying constant. Price changes then depend on how much the exchange value of money changes relative to the exchange value of other commodities. Worth repeating: change values are the total direct and indirect labor time require to produce a commodity.

Money circulation as a very risky circus trick

C-M-C is how Marx symbolically represents commodities being transformed into money and then back into commodities.

C-M repaints sellers of commodities getting money.

Marx says that “The leap taken by value from the body of the commodity, into the body of the gold, is, as I have elsewhere called it, the salto mortale of the commodity. If it falls short, then, although the commodity itself is not harmed, its owner decidedly is.”

“Salto mortale” refers to a dangerous trapeze trick.

A producer may try to sell products at outdated prices as his competitors oversaturate the market, or the product may become obsolete, saddling him with products he can’t sell.

So Marx is here analyzing a version of capitalism in which what standard economics texts call “perfect competition” is the norm. There are many buyers and sellers, and nobody has the power to raise or lower market prices on their own. This is upper Hell he is evaluating, where the sinners lack control of themselves (see the openning section of these notes).

Then Marx examines the M-C portion.

He says that money (as opposed to barter) ends up breaking restrictions (local and personal bonds) that would otherwise limit the circulation of commodities. That creates an ever growing interdependence among buyers and sellers that none can control as money constantly circulates.

It is only because the farmer has sold his wheat that the weaver is enabled to sell his linen, only because the weaver has sold his linen that our Hotspur is enabled to sell his Bible….

The capitalist way of producing commodities drives the need to effectively circulate a great many of them: ie the need for money. The implication is that it would be pointless to abolish money without abolishing capitalist commodity production:

.When one commodity replaces another, the money-commodity always sticks to the hands of some third person. Circulation sweats money from every pore.

Velocity of money and hoarding

If a commodity is exchanged for money but then it takes too long for that money to get exchanged again for commodity then crisis ensues.

…if the split between the sale and the purchase become too pronounced, the intimate connection between them, their oneness, asserts itself by producing - a crisis.

And he introduces a concept of “velocity” of money. For now his idea of how much money is in circulation ignores savings and any kind of banking system- so he is not talking about the total money supply or how a banking system expands it.

He says you can have 1) more money transactions because there are more commodities or 2) more money transactions because the transactions happen more quickly for the same number of commodities (I sell 20 yards of linen then buy a bible in a day instead of over a period of two days for example).

Marx stresses that nominal prices depend on how many commodities the economy produces, how quickly transactions take place, and the value of the precious metal used as money. He quickly notes that the introduction of paper money does not change his analysis. The quantity of paper money like the quantity of gold coins circulating can raise or lower nominal prices.

He says hoarding precious metals increases demand for them and thereby ensures that there is sufficient gold or silver available above what is required for circulation. That facilitates the removal of money from circulation when that may be useful, and creates a reserve supply that can be useful to have in times of crisis. Interesting that he doesn’t talk against hoarding here.

Money allows greater complexity and potential for crisis

Introduces more complexity into the discussion - when consumers buy things without fully paying for them right away - thereby making sellers into creditors. Money facilitates that complexity and increases class conflict between people who lend or owe money. He observes that a disturbance in the credit system based on money has been known to bring down the real economy. Recognizes how easily money expands beyond commodity transactions to payment of taxes and rent. To sum up, advanced production of commodities goes hand in hand with development of a money-based credit system prone to crisis which he says is a problem less advanced economies avoided.

He says that pure undebased, undiluted, unstamped gold is used for int’l trade.

ASIDE on “race”: Footnote 2 refers to “savages and half-civilized races…” usage that betrays a casual European bigotry in Marx but you take all such bigotry out of Das Capital and you’ll be left with 99.999% of the book.

The word “race” appears 19 times in the book. Eleven of those refer to “human race”

He once refers to workers as a “race”

“Hence the sum of the means of subsistence necessary for the production of labour-power must include the means necessary for the labourer's substitutes, i.e., his children, in order that this race of peculiar commodity-owners may perpetuate its appearance in the market”

Another time Marx quotes from a study that found appalling conditions among workers and the report quoted referred to them as a race:

“See "Public Health. Sixth Report of the Medical Officer of the Privy Council, 1863." Published in London 1864. This report deals especially with the agricultural labourers. "Sutherland ... is commonly represented as a highly improved county ... but ... recent inquiry has discovered that even there, in districts once famous for fine men and gallant soldiers, the inhabitants have degenerated into a meagre and stunted race.."

This got overly long even for me, apologies. But I think cutting it down would actually make it more difficult to read. This is post 3/3 so best start at the bottom.

Conclusion

Personally, I find the focus of levels 1-2 essential and incredibly useful, especially from an ethical and activist standpoint; while level 3 (and perhaps the weakest possible version of 4) is merely an important reminder of just how brutal capitalism is (for everyone, really) precisely when operating under idealized conditions where markets aren't hopelessly rigged.

I am unsure of the value ;-) of entering into empirical debates at all in relation to the LTV; I do think that debates for and against the LTV are first and foremost about commitment to an analytical perspective, and rather far removed from datasets. Historically, economists certainly haven't shunned the LTV for problems with accommodating empirical findings.

I tried to tease apart the 4 levels mostly to clarify this for myself. In practice, empirical discussions in economics quickly get into the weeds and smell of argument from authority; hence may turn people off. Consequently I would actually prefer talking of a weaker cousin of the LTV, a LPV - Labor Perspective to Value.

This is enough for me, I tend to be turned off when Marxists still traffic in historical necessities - which are, to be fair, present in the text. But that is subjective and likely I am missing a lot of points of historical significance ;-)

Levels of what we mean by the Labor Theory of Value

LTV level (1): A commitment to a *perspective* on the circular process behind commodity markets where consumers chase low prices and producers look to make a cut, both adjusting their behavior constantly. The LTV clearly foregrounds "supply": where a product is coming from and what its production entailed - really what making an equivalent product would generically entail under average conditions. Within production, the LTV has a sub-focus on human labor [especially wages and working hours] over other aspects ("inputs") such as energy and land use. [Note that pollution and hogging of resources such as water also have obvious impacts on human (and animal) welfare more generally].

It is already at this basic level that the LTV is the mirror image of the prevailing perspective in "mainstream" economic "science" which foregrounds demand - to the point that "market fundamentalists" insist that whatever the market "says" is the "true" price of a commodity: who are you to question the will of the market?

I think we can rightly insist on foregrounding the human element in production/supply in effectively any and all discussions related to (political) economy. To skip over this is almost a deliberate act of putting on blinders to un-see inhumane practices. It is on this basic level here the ethical commitment is strongest. Note that this perspective - any perspective really - is valid quite irrespective of the empirical record of mechanics underlying commodity prices.

LTV (2) An explanatory principle of how commodity prices come about and the class war they reflect.

The insistence on labor as the linchpin of analysis makes possible to define the surplus created at each step of production - and crucially to then ask how the surplus is distributed between workers (wages) and owners (profit to be re-invested or extracted).

[We can expand this perspective to include more classes by looking more closely into how wages are distributed, including wages for workers who do the actual work compared to those who do related organizational work, those who merely keep the workers in line, oversee the extraction of profits, salaries of senior management, etc.]

I think this is the heart of Marx' general project in Kapital. In my experience it is primarily this question of distribution of surpluses where Marxian economics shines - and which is behind its detractors instinctive dismissal of the whole package. To be fair, the concept of "surplus" is somewhat arcane in a world where "profit margin" is front and center in trade magazines and popular culture.

Note that a strong explanatory principle such as the LTV can in principle explain anything - we can express any sentence in any sufficiently complex language. This is the very strength of explanatory principles. As a corollary, also market fundamentalists can explain absolutely anything in terms of market demand if they put their mind to it. Outside of the theoretical focus the explanation becomes merely more and more awkward ;-):

We can explain the lack of eggs on the market due to the number of hens that had to be culled due to bird flu - we can in principle also insist that hens themselves hatch from eggs so "ultimately" we needed to reserve eggs to replenish the stock of laying hens. (Both perspectives have the same claim on truth and certainly cannot be distinguished empirically).

I commend Joe for his beautifully awkward illustration quoted above: collapsing prices for violins merely correlating with lack of demand for violins while "really" "ultimately" due to collapsing working hours spent making violins. This shows that the LTV is working and can indeed correctly explain anything.

Personally I would prefer to be pluralistic in such edge cases and couch our explanation in terms of demand directly whenever convenient - while insisting on making explicit the impact of lack of consumer buying power on people making and maintaining violins - as well as musicians, conductors, teachers, art critics, etc.

LTV level (3) Commodity prices do in fact tend to get determined by the cost of human labor (keeping in mind that multiple factors play a role) - at least under certain conditions such as competitive markets with low barriers of entry etc.

The way I read Marx (please correct me if I am wrong), there is a general principle at work: if a capitalists sells a commodity with a high profit margin, other capitalists will notice this business opportunity and get into production themselves. This will drive down profit margins. Eventually commodity prices will come to reflect the price of production [and within production, the cost of human labor] plus a much reduced profit margin.

This is an empirical claim - really a theoretical framework for making models that make testable claims. As such it is mostly for practitioners to evaluate the usefulness of this construction. Note that theoretical frameworks cannot really be directly tested and the devil is in the details.

Also note that it will depend on what a modeler wants to achieve with a model, what data are available and so on. For example, quite often modelers are interested in explaining the difference between particular prices rather than in their ultimate nature; they may well find that variations in prices are mostly "explained" e.g. by differences in climatic conditions. This would still have little bearing on the LTV as there may well not have been any variation in "human capital" i.e. wages and working hours are fixed through minimum wage legislation or union contracts generally followed in the industry. So from this particular dataset we would have no way of knowing whether changes in relative wages would drive changes in commodity prices.

It probably has become clear that I am deficient in that I am just not very much invested in the nitty-gritty of making and testing such models - I am not an economist or trader.

My own sense is that the empirical project of looking at whether particular prices are actually strongly determined by wage levels (Ian Wright referenced by Joe here) is less a test "of the LTV" but rather an evaluation of whether a particular segment of "the market" is somewhat "competitive". As such it is really interesting and useful, don't get me wrong. However it is hardly specific to the LTV, also e.g. neo-classical economists can evaluate whether a market is "functioning"; unless of course they are market fundamentalists in which case the market is always functioning perfectly: who are you to question the will of the market?

Generally I also find a (perhaps overly reflexive) defense of level (3) of the LTV a bit ironic given recent history:

The neo-classicals famously have (had?) a fetish: the mathematical notion of market equilibrium that - no matter what - is guaranteed to drive prices "in the long run". They were equally famously lambasted by Keynes: "In the long run we are all dead".

Similarly, I think there are many decisions to be made or debates to be had that in practice cannot wait for (distorted) prices to come to reflect more regular price mechanisms - even if it were possible to demonstrate that general price mechanics are fully captured by the LTV, and by the LTV alone, for actually existing markets from the 19th to the 21th century.

LTV (4) Long term trends, in particular the tendency of profits to fall, at least in mature industries

This is the most tenuous level of application of the LTV. The way I see it is perfectly possible to subscribe to levels 1-3 of the LTV without a commitment to diagnosing long term systemic trends.

It is both the strength and the limitation of Marx' works that already his introduction kind of fractally embodies his whole theoretical construction, which is why I am making this explicit here as an (optional) level (even though we are probably getting ahead of ourselves in terms of chapters in the book).

I must say I am not quite clear on whether falling rates of profits were an empirical finding first - in need of theoretical explanation; or whether Marx' theorizing was an impetus for following those rates over time - which would count as evidence in favor of his theories (to the extent that this is really a general phenomenon).

Generally prediction is difficult, especially about the future, and I think we now have a much more modest view of the predictive power of theories and models in systems sciences.

Even if we relax the scope of "historical necessity" etc., if nothing else Marx beautifully highlight the seeds of chaos inherent in capitalism, crucial again in a time well after the beast had been superficially tamed in selected places for a few decades.