STUDYING DAS KAPITAL: Part 3 (of 8)

Summarizing , mostly defending and, at times, critiquing Volume I

Chapter 7: The Labour-Process and the Process of Producing Surplus Value

This chapter marks the beginning of Part 3: The Production of Absolute Surplus Value. It includes chapters 7 through 11. If you prefer to download a PDF with all eight parts of my study notes combined into a single document, click the button below to do that.

He introduces the term “instruments of production”, and defines the earth itself as a “universal instrument” so he is looking at human-made and non-human made things under this category.

Then he proceeds to define “means of production” much more broadly than he has done until this point so that it includes the instruments of production. Products we think of as natural are impacted by human production such as seed and domesticated animals.

Anticipating the essential element of Piero Sraffa’s analysis almost 100 years later (Staffa wrote “The Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities” in 1960) Marx stresses that commodities are required to produce commodities. Corn, cattle, and coal are examples he gives of commodities that are essential inputs to production as well as final consumption.

An example of surplus value production

Reiterating key concepts, Marx says a capitalist aims to produce a commodity that has a use-value and therefore an exchange value. But capitalists also seek to have the exchange value of the commodity exceed the exchange value of the means of production and the labour power that goes into making it. In short, the capitalist pursues surplus value.

The “means of production” is defined by Marx as raw materials and machinery (and presumably all other tools).

Marx stresses that, while labor time is exchange value, a capitalist does not create more exchange value by using more labor time than is necessary: for example by letting his workers get away with working at below average speed. Socially necessary labour time is the basis of exchange value of any commodity. (Similarly, he says the capitalist does not increase exchange value by using a gold spindle when only a steel spindle is required) In fact, socially necessary labour time is also the basis for the exchange value of human labour itself: it takes labor time to produce the food, clothing, shelter, heat (in regions with cold winters) required to maintain a work force.

Marx asks us to imagine a capitalist ranting in frustration that all he gets back from selling his commodities is the exchange value of his raw materials, the wear on his machines and tools, and the wages he paid out. If all the capitalist gets back is what he put in then why bother? Marx offers the answer through an example in which the exchange value of a worker is equal to ½ workday’s labour time. That means it takes ½ day of labour to keep each worker alive and healthy enough to work. But the employer gets him to work for the full day.

What Marx pinpoints is the difference between the exchange value of labor and the use-value of labour that is purchased by the capitalist. Marx continues

The seller of labour-power, like the seller of any other commodity, realises its exchange- value, and parts with its use-value. He cannot take the one without giving the other. The use-value of labour-power, or in other words, labour, belongs just as little to its seller, as the use-value of oil after it has been sold belongs to the dealer who has sold it.

So Marx did know that the purchasers of all commodities usually get more use-value than they give up in exchange-value. Any standard economics text that talks about “Consumer surplus” explains a similar concept. Marx’s objection to capitalism is that it is disastrous for workers, who are human beings - not inanimate objects - to give up ownership of their use-values as workers.

Marx goes on to illustrate in a numerical example.

The cost of the cotton plus wear on the spindle that produces 10 lbs of yarn is equal to 2 days of labour. And half day (6 hours because the workday length is 12 hours) is required for the workers to spin 10 lbs of cotton into yarn. So 2.5 days is the total cost in labour time of raw material, machine wear and labour. In monetary terms, Marx chose proportionate numbers for the example - 15 shillings worth of yarn was produced (3 shillings went to pay workers and 12 shillings covers raw material and machine wear). If the workday were only 6 hours long the capitalist would not see any surplus value. The capitalist would pay 15 shillings to get back 15 shillings.

But by the time the workers have worked the entire 12 hour day they have produced 20 lbs of yarn worth 30 shillings. The capitalist has then spent 24 shilling on means of production but still only 3 shillings on workers. He has therefore spent 27 shillings to produce yarn worth 30 shillings, so 3 shillings of surplus value was created.

Marx finishes by saying that for simplicity skilled labor can be neglected. His last footnote for this chapter elaborates on this. Indeed, Marx is correct that the skill level and size of the professional class is often overhyped. He should have added that the difficulty of “ordinary” jobs, and the amount of innovation the “unskilled” do to keep production running, goes unrecognized. That said, skilled labour has a higher exchange value due to the labour time required to train and regulate skilled workers.Hence the capitalist’s incentive to de-skill the workforce which Marx discusses later in the book.

ASIDE: Bertrand Russell wrote that Marx criticized the extraction of surplus value from workers but ignored that the same is done to products: buyers get more use-value from them than exchange value.

This is a very bad argument by Russell. Yes, capitalists also extract more use-value than exchange value from raw materials and other inputs, but nobody argues for giving ownership of the means of production to inanimate objects. Is a guitar exploited by the person who buys one? As the economist Bill Mitchell put it “Bosses have to control the realization of that use value as production in an environment where the majority of workers would rather not be there. That is a very different dynamic environment to one where we go into a shop and buy a trinket to be enjoyed later.”

Economist Steve Keen applied Russell’s argument more thoughtfully to dispute that human labour is the only input that should be credited with creating surplus value. But it is, in fact, the only input that should be credited, as explained here. All inputs like tools, machines, buildings, roads were made by human labor. All failures by machines or other non-human inputs are ultimately human failures. And human workers are the only input (even today when sophisticated robots and computers exist) that are capable of innovating within any production process.

Chapter 8: Constant Capital and Variable Capital

Marx defines constant capital as the money the capitalist spends on raw materials, tools, machines etc..in short, the “means of production”. He refers to it as constant because its exchange value does not change as a result of the production process. It has exchange value due to past labour that went into producing it. Its exchange value is “transferred and preserved” in the new commodity that workers create during the production process.

Variable capital is what capitalists spend on workers on the job today who transfer and preserve the exchange value of the means of production to create new exchange value. The new exchange value is sufficient to cover wages and an extra amount, surplus value. But how much surplus value is created (and note that it is only created by workers on the job today) is variable. Its amount depends on factors that Marx will elaborate on later. He therefore calls the money spent on workers today “variable capital”.

Recall that in Chapter 1 Marx said “However then productive power may vary, the same labour, exercised during equal periods of time, always yields equal amounts of [exchange] value. But it will yield, during equal periods of time, different quantities of values in use” In any given hour, the worker always adds the same amount of new exchange value. If workers’ productivity increases then they will “transfer and preserve” more of the old exchange value from the raw materials, tools, machines, etc… So the total exchange value that results from their hour of work - old plus new exchange value - increases if their productivity increases.

He then says that if productivity is constant but means of production exchange values go up or down then it can have the same net impact on the total exchange value produced as a change in productivity. Note that the exchange values of the means of production can change, but not because of the production process which is why Marx refers to the means of production as “constant” capital.

Chapter 9: The Rate of Surplus value

Capital, C, is the money the capitalist spends on the means of production (constant capital, c) and wages (variable capital, v): C = c + v

Through the production process C becomes C’ which includes s, surplus value:

C’ = c + v + s

If c=0 that means the industry (fruit picking may be an example) uses negligible means of production. Also, as discussed in the last chapter, new exchange value is produced only by workers during the production process. The new exchange value includes all the new surplus value they create. The exchange value contained in the means of production (the creation of the workers who produced those items) merely gets transferred and preserved by workers who use them. Therefore surplus value is “an increment of v”:

v + s = v + dv, where dv is an increment of v.

Marx defines the ratio s / v as the “rate of surplus value”. It is “an exact expression for the degree of exploitation of labour- power by capital, or of the labourer by the capitalist”. He says the ratio s / (c + v) is also very important, and that it will be looked at very closely in Vol III. Indeed s / (c +v) became central to Marx’s flawed attempt to show in Volume III that prices were proportional to labour time. Showing that was essential to defending the labour theory of value. For a discussion of the problems with Marx’s proof and how they were resolved by the Marxist scholar Ian Wright, read this essay.

In terms of labour time,

s/v = surplus labour / necessary labour.

Necessary labour time is the time required for workers to earn enough to survive. For the capitalist this labour is “necessary” for workers to keep coming back to work. Surplus labour is the time period when workers produce surplus value.

Numerical example

He then gives a detailed example of a factory spinning cotton into yarn. The units below are all English pounds.

v = wages = 52 per week

c = weekly raw mat’l cost of 342 + wear & tear on spindles 20 + rent 6 + coal consumption for heating and spindle operation (for powering steam engine) 4.5 + gas 1 + oil 4.5 = 378

C’ = quantity of yarn produced per week, so quantity multiplied by its selling price = 510

s = C’ - c - v = 510 - 378 - 52 = 80

s / v = 80 / 52 = 1.538

Therefore surplus labour / necessary labour = 1.538

If the workday is 10 hours then

necessary labour + surplus labour = 10

We therefore have two equations above for necessary labour and surplus labour. We can now solve for both.

In a 10 hour day workers spend just over 6.06 hours creating surplus value for the capitalist and 3.94 hrs making their wage. If s/v were 1 it would be 5 hours. The capitalist wants s/v to be as high as possible

Another numerical example

Marx returns to an example from Chapter 6 and breaks down the value portions of 20 lbs of yarn produced from 20 lbs of cotton. The units below “s” stand for shillings

30s. value of yarn = 24s. const. + 3s. var. + 3s. surpl.

He notes that if you convert these values in shillings into equivalent weights of cotton then it is as if the 20 lb of yarn contains only 13 1/3 lbs of cotton (because 24s breaks down into 20s of cotton + 4s wear and tear on spindle) or to put it in terms of his equation

30s value of yarn (20 lb) = 24s (16lb) const + 3s (2 lb) var + 3s (2lb) surpl

By value 24s (16lb) const = 20s (13 1/3lb) cotton + 4s (2 ⅔lb) spindle wear

And if you similarly split up the 20 lb of yarn worth 30s into proportionate equivalents of the 12 hour work day you get

30s (60 hours) = 24s (48 hours) const + 3s (6hours) var + 3s (6 hours) surpl

And this breakdown, Marx noted, can be misused to make spurious anti-worker arguments.

Senior's "Last Hour"

Marx then gives the example of an economist (Nassau Senior) who fought against legislation to limit the workday to 10 hours. Senior argued that it was only in the last hour of the day that capitalists profit.

Marx said Senior ignored that shortening the workday reduced the capitalists’ consumption of the means of production. A workday shortened to 10 hours therefore scaled down but did not come close to eliminating their profits. Marx said workers covered their wages in just under 6 hours, so that 4 hours of the day was still spent producing surplus value.

Thus far in the book, details about the horrors of capitalism are mainly reserved for the footnotes. The text, for the most part, contains unemotive analysis. The last footnote of this chapter describes the horrific conditions in factories where capitalists employed children. These capitalists, Marx observed with obvious disgust, objected to a reduction in the workday by arguing that extra leisure time would bad for the children’s’ moral development,

ASIDE: Does “surplus value” go away if all means of production are collectively owned and truly run for the benefit of all? There would still be a difference in such a society between what workers are paid and the use-value obtained from workers - even though that difference is owned by everyone.

Marx touches on this at the end of Chapter 17:

“Only by suppressing the capitalist form of production could the length of the working day be reduced to the necessary labour time. But, even in that case, the latter would extend its limits. On the one hand, because the notion of "means of subsistence" would considerably expand, and the labourer would lay claim to an altogether different standard of life. On the other hand, because a part of what is now surplus labour, would then count as necessary labour; I mean the labour of forming a fund for reserve and accumulation.”

With capitalism gone workers will claim a better lifestyle but, collectively,will still have to invest for the future.

Chapter 10: The Working day

Section 1: The Limits of the Working day

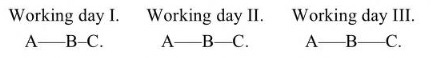

Marx uses the line segments above to represent work days of increasing length: 7 hours, 9 hours, and 12 hours. In each case, line segment AB has the same length. It represents 6 hours of “necessary labour”. Segment BC represents surplus labour. It grows as the workday lengthens. BC/AB is s /v, the rate of exploitation

The length of the work day has physical limits.There are only 24 hours in a day. Workers must take some time to sleep and eat. And society eventually imposes moral limits, but there is wide variation in those limits: “So we find working days of 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18 hours”. In describing the capitalist’s attitude towards the length of the workday, Marx now brings some rhetorical fire into the text that he has mainly kept to the footnotes:

As a capitalist, he is only capital personified. His soul is the soul of capital. But capital has one single life impulse, the tendency to create value and surplus value, to make its constant factor, the means of production, absorb the greatest possible amount of surplus labour. Capital is dead labour, that, vampire-like, only lives by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks.

Marx points out that labour-power is a peculiar commodity in that societies impose limits to the buyer’s consumption of it. Nobody tells you how much of the food you buy you are allowed to eat.

Section 2: The Greed for Surplus-Labor, Manufacturer and

Boyard

Capitalism did not create surplus labor. In feudal societies the serfs had to work to produce a surplus of their lords (and a Wallachian Boyard was one type of lord). Marx says this happens whenever “a part of society possesses the monopoly of the means of production”. But with capitalism the greed for surplus labour is much worse. He notes that slavery in the southern US was made even more brutal by capitalism - as the export of cotton became the key objective (rather than just satisfying the local market).

Marx says legislation passed in England limited work days to 10 hours and appointed factory inspectors for rational reasons: to prevent civil unrest and the spread of disease. He then quotes details of inspector reports on the disgusting way the bosses tried to circumvent minimalist laws: “These ‘small thefts’ of capital from the labourer's meal and recreation time, the factory inspectors also designate as ‘petty pilferings of minutes’. Marx was repulsed by child labor and makes frequent mention of in this chapter and in the book as a whole: “Nothing is from this point of view more characteristic than the designation of the workers who work full time as ‘full-timers,’ and the children under 13 who are only allowed to work 6 hours as ‘half-timers.’ The worker is here nothing more than personified labour-time.“

Section 3: Branches of English Industry Without Legal Limits to Exploitation

Marx quotes extensively from English inspector reports of 1860 and 1863. Much of the testimony in these reports come from doctors and child workers: children as young as 5 years old working, workdays as long as 15 hours, meals taken in rooms contaminated with phosphorus. Marx comments that “Dante would have found the worst horrors of his Inferno surpassed in this manufacture”.

On top of that businesses got away with selling bread to workers that was “adulterated” with items like human perspiration, cobwebs, dead black-beetles, and sand.

In another passage Marx expresses dismay at railway workers being found guilty of manslaughter when, as a result of extreme overwork demanded by their bosses, an accident killed hundreds of passengers. What particularly appalled Marx was the “gentle ‘rider’ to their verdict, expressed the pious hope that the capitalistic magnates of the railways would, in future, be more extravagant in the purchase of a sufficient quantity of labour-power, and more ‘abstemious,’ more ‘self-denying,’ more ‘thrifty,’ in the draining of paid labour-power.”

Marx mentions a London newspaper headline from 1863 that openly stated “Death from simple over-work" regarding a 20 year old worker who was, as Marx put it, “exploited by a lady with the pleasant name of Elise.”

ASIDE: Bertrand Russell once dismissed Das Kapital as “atrocity stories” saying Marx was right about abuses but that he didn’t prove things would be better under Communism. But the “proof” for the implied alternative is unassailable: take control of means of production away from an inevitably exploitative business focussed on profits. In fact, Russell , even more absurdly, accused Marx of causing class warfare:

…a collection of atrocity stories designed to stimulate martial ardour against the enemy. Very naturally, it also stimulates the martial ardour of the enemy. It thus brings, about the classwar which it prophesies. It is through the stimulation of hatred that Marx has proved such a tremendous political force, and through the fact that he has successfully represented capitalists as objects of moral abhorrence.

People are rational and do not passively accept murderous exploitation. Marx chose a side in the class war. Russell chose the opposite one. Russell was a president of the CIA front group The Congress for Cultural Freedom.

Section 4: Day and Night Work. The Relay System

Marx discusses shift work as a way to quench capitalism’s insatiable “vampire thirst” to suck surplus value from workers. And he cites detailed testimony, much of it about child labour - what Russell dismissed as “atrocity stories”.

Section 5: The Struggle for a Normal Working Day. Compulsory Laws for the Extension of the Working Day from the Middle of the 14th to the End of the 17th Century

Marx again backs this rhetoric up with extensive factual reporting of capitalist atrocities in his day. Marx observes that it is very difficult for capitalists to be hurt by killing off its workers. If capitalist brutality causes a labor shortage problem for itself, then brutality is deployed to fix it: “the manufacturers proposed to the Poor Law Commissioners that they should send the ‘surplus-population’ of the agricultural districts to the north, with the explanation ‘that the manufacturers would absorb and use it up’ ".

In pre-capitalist and early capitalist eras the state tried to lengthen the workday, but as capitalists advanced the state was forced to try to shorten the workday to prevent civil unrest. It would be pointless for individual capitalists to try to shorten the workday voluntarily and be outcompeted by rivals who don’t given the “external coercive laws having power over every individual capitalist” So the state increasingly stepped in, weakly, to “prevent the coining of children's blood into capital.”

In 1833 the English Parliament “reduced the working day for children of 13 to 18, in four branches of industry to 12 full hours”. Marx noted that “houses of terror” where the poor were tortured with work in 1770 were barely worse than what the minimum the British state tried to impose on capitalists 63 years later.

Section 6: The Struggle for a Normal Working Day. Compulsory Limitation by Law of the Working-Time. English Factory Acts, 1833

Marx explains how capitalists, with the complicity of government, ensured that the 1883 reforms were circumvented. The government would not pay for enough inspectors to enforce them. Marx ridicules how the state gradually increased the age limit at which a maximum 8 hour work day applied. The age limit increased from 11 years of age to 13 between 1834 to 1836. The state was worried about too quickly imposing reforms that were barbarically inadequate - and that capitalists were openly disregarding. And the state did this despite warnings from an imminent London physician that timely action was required “for the prevention of death”.

Corn laws (trade restrictions) kept bread prices high (benefitting the landed aristocracy) so manufacturers opposed the corn laws to try to get workers to join them in opposing the Factory Acts. Lower bread prices would help keep wages down. The landowners then claimed to champion factory reform.

In 1844, by actually legislating some protection of adults, some big loopholes were closed in the child labor laws. Manufacturers countered by getting parliament to lower the legal age for work from 9 years of age to 8.

During 1846-47, Tories (who were mostly landed aristocrats) got revenge on manufacturers for the repeal of Corn Laws by helping reduce the legal workday to 10 hours. Marx reviews the manufacturers’ counter-attack which included coerced testimony against the Act from workers, and the vilification of factory inspectors in the press.

But then an insurrection in Paris scared the ruling classes of the UK into uniting against reform. They launched what Marx called “a pro-slavery rebellion in miniature, carried on for over two years with a cynical recklessness, a terrorist energy all the cheaper because the rebel capitalist risked nothing except the skin of his ‘hands.’ “ Factory inspectors uselessly appealed to the courts where “masters sat in judgment on themselves”. Marx blasts the hypocrisy of manufacturers who rallied workers to support anti-Corn Law legislation but then fought viciously to ensure that all the benefits from that were pocketed by manufaturers, not workers.

From 1833 until the time Marx was writing Das Kapital, silk manufacturers were especially aggressive to get children workers due to their little fingers, and got exemptions to the (already barbaric) laws made for them. Marx comments “The children were slaughtered out-and-out for the sake of their delicate fingers”.

Section 7: The Struggle for a Normal Working Day. Reaction of the English Factory Acts on Other Countries

Marx draws these conclusions: First, new technology gave capitalists the ability to exploit labor like never before, but it led to worker resistance. That led to legislation aimed at limiting exploitation - especially as factory-style production systems spread to other industries that were not as advanced.

Second, capitalism inevitably behaves like a vampire predator squeezing life out of workers, so workers must unite, including across racial lines, to fight off the predator: Marx says “In the United States of North America, every independent movement of the workers was paralysed so long as slavery disfigured a part of the Republic. Labour cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded.”

Chapter 11 : Rate and Mass of Surplus Value

He defines S, as the “mass of the surplus value” produced in a day by a group of workers.

The term “s” is surplus value produced per worker per day. The term “n” is the number of workers. The term “v” is the variable capital advanced per worker per day. V is the variable capital advanced to get “n” workers for one day.

By his definitions S = sn and V = vn. Substituting vn for V on the right side above makes it reduce to S = sn, consistent with his definitions. In the second equation about, which, for brevity, we will ignore, P is the same as v and (a’/a) is the same as s/v.

Can a capitalist always increase S by the same proportion he increases n, the number of workers he hires? No, because the “value of their labor-power” may fall. Marx failed to say productivity and we can only assume this is what he meant. Wages may remain constant but the capitalist may overhire and not be able to use extra workers efficiently (too little space for them, not enough tools for them).

Marx then gives numerical examples, the importance of which is to illustrate what makes S increase or decrease.

Given a 6 hour work day, n=100 workers, V = 300, s/v =0.5 (or 50%) therefore S = (s/v) V = 300 (0.5) = 150

Note that the surplus value part of the work day (s) in the example above would be 2 hours, the necessary labour time (v) would be 4 since s/v = 0.5. Confusingly, Marx states that S represents 100 x 3 working hours. That’s not wrong but needlessly confusing. Yes, the capitalist hires 100 workers for 6 hours using 300 shillings. Therefore 150 shilling (the value of S) is equal to what the capitalist would have had to spend to hire 300 workers for 3 hours.

He then says we can also get S= 150 if V is 150 (because the work day has been extended and the capitalist needs half the number of workers ). The rate of exploitation doubles (s/v = 1) and S remains equal to 150.

Two more examples follow that use the same relation between V and n (V=300 was sufficient to hire 100 workers).

EXAMPLE A

s/v=1, V=1500 (therefore n=500), S = (s/v)*V = 1500

If there is a 12 hour day this would mean 6 hours produce surplus value

EXAMPLE B

s/v=2, V=300 (therefore n=100), S = (s/v)*V = 600

If the work day is 18 hours long then surplus value time is 12 hours

So going from example A to example B things the capitalist likes such as a rise in s/v and also the length of workday were more than offset by fewer workers being employed. S ended up being smaller

Marx promises to explain later on why this limit doesn’t stop capitalists from relentlessly trying to cut the number of workers they employ. Marx observes that the capitalist may not be able to increase the number of workers by a sufficiently large percentage in response to falling s/v and falling workday length - and that S may therefore fall. And of course there are only 24 hours in the day. He reminds us that S does not include constant capital because S is new value added by workers not the previously existing value they transfer and preserve from the means of production.

Marx says it takes a minimum amount of money to be a capitalist. If a capitalists can only afford 1 worker, and he gets 4 hours of surplus value out of him, then he needs two workers to be able to live off them only as well as a worker - to get 8 hours of surplus value out of them every day. To live twice as well and “turn half his surplus value into capital” he would need to live off 8 workers since he would need a total of 32 hours of surplus value out of them,16 for himself and 16 to use as capital. He notes that the middle age guilds had strict limits on how many of the trade could work for others. Sometimes, this minimum money to be a capitalist in some fields is so large that the state supplies it.

Capitalism stands out, says Marx, through both “recklessness and efficiency” compared to earlier systems of compulsory labour.

Marx ends the chapter by making fun of a Scottish manufacturer who wrote to a newspaper complaining that if he sold his machinery it would be worth 10/12 of its previous value if the workday was shortened from 12 hours down to 10. Marx’s argument against this Scotsman was based on the labor theory of value - workers becoming a bit more scarce (through shortening the work day) does not reduce the labour time required to make the machine.

hell yeah! David Harvey's “companion to capital” was a big help to me getting thru it the first time