STUDYING DAS KAPITAL: Part 4 (of 8)

Summarizing , mostly defending and, at times, critiquing Volume I

Chapter 12: The Concept of Relative Surplus Value

Part 4 of the book, the longest of the eight parts, is called “The Production of Relative Surplus Value”. It contains chapters 12 through 15. If you prefer to download a PDF with all eight parts of my study notes combined into a single document, click the button below to do that.

At the start of Chapter 12, Marx shows a line segment where ac is the length of the workday and it is fixed in length: ab is necessary labor time at an old value of labour power; ab’ is necessary labour time at a reduced value of labour-power. Segments bc and b’c are the old and new surplus labour times, respectively.

a----b’--b-----c

If you know the hourly wage of the workers and the length of the day you can easily calculate how much of the workday is surplus versus necessary labour time. An example Marx gives is summed up as follows:

Hourly wage = sixpence (1/2 shilling); If 5 shillings per worker per day is enough for workers to live on, then that means each worker must put in 10 hours to make that. Therefore if the workday is 12 hours, surplus labour accounts for 2 hours of it.

Marx adds that employers can underpay, but he is assuming for now that it doesn’t happen. Increased productivity in the fields that determine the exchange value of labour is the way to increase the surplus labor portion of the workday if the workday is fixed in length - because those productivity gains reduce the exchange value of labour-power.

He calls extra surplus value produced by lengthening the workday “absolute surplus value”. He calls extra surplus value produced by reducing necessary labor time “relative surplus value”. He stresses that relative surplus value results from increased productivity in the fields that supply “necessities of life” to workers. ASIDE: A better formulation of this would be “the consumption basket of workers” since what constitutes “necessities” can change dramatically depending on the bargaining power of workers.

Another numerical example below, as Marx explores what happens within industries where productivity increases:

1 hr labour = sixpence (½ shilling) Therefore 6 shillings of new exchange value produced in a 12 hr workday.

That means v + s = 6

Suppose 12 articles are produced in a workday. Constant capital used up per article is ½, so for the work day, c= 12(½) =6

Hence the total value of the articles = c + v + s= 6 + 6 = 12, or 1 shilling per article

In the next example productivity doubles so that 24 articles are produced in a workday.

In that case c= 24(½) = 12 but v+s is still 6. Therefore c+ v + s = 12 +6 = 18, or ¾ shilling per article

Marx considers the case where only one firm, as opposed to all firms who make these articles, discovers a way to increase productivity. Marx then stresses that one firm can sell its product at the going price (which it alone cannot change since Marx is still analyzing a capitalist system where markets are highly competitive) for a greater profit per article. But the firm will also want to sell everything it has made. To do that, the firm will want to lower the price a bit..

Another example explores follows in which Marx gives slightly different information - and is more specific about s/v :

To hire a worker for a 12 hour work day costs 5 shillings (v=5); 10 hrs is necessary labor time; 2 hrs surplus value time. Hence s/v=0.2 Therefore in money terms surplus value (s) = 1 shilling. This means v+s = 6 for the 12 articles

c= 12(½)=6

c+v+s = 12, or 1 shilling per article

When productivity increases to 24 articles, they are sold at tenpence each (0.8333 shillings). That’s below the 1 shilling price other firms sell at, but above the ¾ shilling cost of the extra productive firm.

Therefore c + v+ s = 240/12 = 20 shillings. But recall that c = 24(½)=12 shillings,

How many articles must be sold at 0.8333 shillings to yield 12 shillings?

The answer is 14.4 articles. That’s the number of articles that pays for c. The remainder, 9.6 articles sold (24-14.4) pays for v + s

Also v = 5 shillings which is paid for by selling 6 articles ( 5/0.8333)

Therefore 3.6 articles sold (9.6-6) pays for surplus value,s, of 3 shillings

Before the productivity increase the ratio of s/v was 0.2

After the increase the s/v = ⅗ =0.6

So the increased productivity has cut into the workers necessary labour portion of the day.

He then adds that competition will eventually force competitors to adopt the new methods. But that the general rate of surplus value is only impacted with increased productivity in industries that impact worker survival costs, which will drive down real wages

ASIDE: Today, many economists would object that this is not the only possible outcome since workers , depending on politics and the unionization rate, can take a significant share of the productivity gains. But neoliberal era shows how effectively the ruling class can claw back those gains even in countries with advanced welfare states. That illustrates that the basic tendency Marx described in his day, when workers definitely would get shafted, still holds. He was writing at a time when small children in England could be worked to death in factories.

Chapter 13: Co-operation

Marx say “When numerous labourers work together side by side, whether in one and the same process, or in different but connected processes, they are said to co-operate, or to work in co-operation” He reiterates that capitalism doesn’t really begin until you have a sufficiently large number of workers producing a great quantity of commodities. He stresses that even without changes in the way people work, simply employing large numbers of workers drives down unit costs - and if the lower costs are part of the workers’ consumption basket that drives down labour costs. Capitalists can then pay workers less without workers having to consume less. He adds that scale of production also impacts the profit rate (the ratio s/ (c+ v) ) but that this will be discussed in Volume III.

He identifies the western USA and India (where he notes “English rule has destroyed the old communities”) as areas where worker co-operation is lacking and inefficiency abounds. But under capitalism as co-operation increases, and more workers are made to consciously work towards the same goal, the number of masters also decreases - a capitalist class is formed. This is especially so since in Marx’s day it was especially necessary for this kind of co-operation to take place with workers under the same roof.

But large scale production creates needs for tight control if surplus value is to be maximized (like an orchestra needs a conductor or an army needs generals are the analogies Marx uses). It thus creates conditions for resistance from workers. It drives the need for a professional class as capitalism develops. Marx again uses an army analogy to explain this - an army needs not only generals and soldiers but also “officers (managers), and sergeants (foremen, overlookers)”.

Marx says that Capitalists tend to give themselves excessive credit for co-operation however. H asks us to remember the large scale production of the pre-capitalist era “simple co-operation are to be seen in the gigantic structures of the ancient Asiatics, Egyptians, Etruscans,”

Chapter 14: Division of Labour and Manufacture

ASIDE: Anti-Marxists like to point out that the most famous Marxist revolutions in the world took place in Russia and China which were still largely agrarian. Was Marx foolish to focus on the revolutionary potential of workers in the manufacturing sector? No, for three reasons.

First, capitalists in the imperial core didn’t allow a labor aristocracy among manufacturing workers to develop out of the goodness of their hearts. Massive concessions were made to stave off the threat of revolution. Review the list of rudimentary demands like universal suffrage that Marx was pressing for when he was interviewed by the Chicago Tribune 1879.

Second, Marx had studied and witnessed huge working class revolts in Europe, notably the Paris Commune.

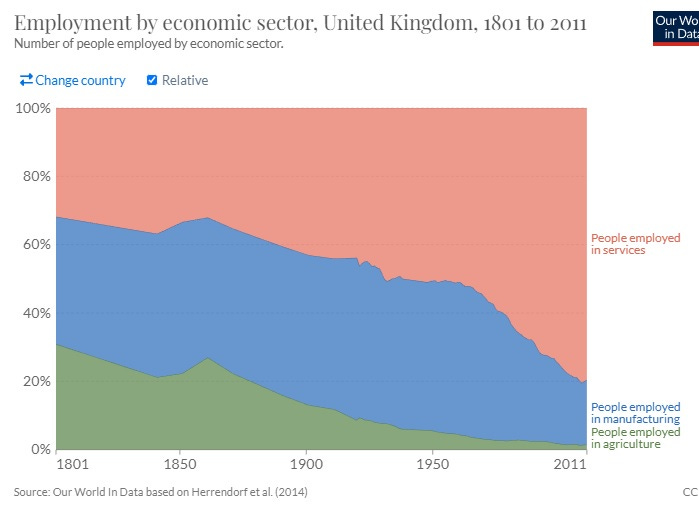

Third, the chart below is worth looking at considering Marx’s focus on the manufacturing sector. It was about a third of employment in the UK when he wrote Das Kapital. It grew to 45% (mainly at the expense of agriculture) by 1900. It stayed at about 45% until a significant downward trend began around 1970. By 2011 it had fallen to 19%.

Section 1: Two-Fold Origin of Manufacture

Early in capitalism, different types of tradesmen began to be gathered to work under one roof. They became collectively more efficient but individually somewhat less skilled since factories made the same kind of product over and over again. Pressure to produce created pressure to deskill workers as the division of labor continued to evolve

Section 2: The Detail Labourer and his Implements

He argues that breaking down skilled tasks into simpler ones “thus creates at the same time one of the material conditions for the existence of machinery, which consists of a combination of simple instruments”

Section 3: The Two Fundamental Forms of Manufacture: Heterogeneous Manufacture, Serial Manufacture

Form 1 “results from the mere mechanical fitting together of partial products made independently” . Form 2 “owes its completed shape to a series of connected processes and manipulations”

He says watch manufacturing is an example of form 1 but argues that a locomotive production cannot be form 1 because its manufacture was already highly mechanized. He goes into a history of manufacturing that cites Adam Smith:

The Roman Empire had handed down the elementary form of all machinery in the water-wheel. The handicraft period bequeathed to us the great inventions of the compass, of gunpowder, of type-printing, and of the automatic clock. But, on the whole, machinery played that subordinate part which Adam Smith assigns to it in comparison with division of labour. The sporadic use of machinery in the 17th century was of the greatest importance, because it supplied the great mathematicians of that time with a practical basis and stimulant to the creation of the science of mechanics.

He stresses again that as manufacturing develops under capitalism deskilling drives down labour costs since training is part of the cost.

Section 4: Division of Labour in Manufacture, and Division of

Labour in Society

He makes general observations about division of labor in a factory compared to the division of labor that exists at a more macro level within different industries: like businesses that supply other industries with raw materials or parts. Within factories, the division of labor is more planned and disciplined.

Marx ridicules capitalist rhetoric about freedom with the iron discipline they want workers to live under in their factories. Capitalists who object to communism basically complain that everyone will be forced to live like a worker in their factories. As Marx put it “ enthusiastic apologists of the factory system have nothing more damning to urge against a general organisation of the labour of society, than that it would turn all society into one immense factory.”

He says that capitalism makes enterprises collectively adopt a chaotic and unplanned social division of labor among firms but a tyrannical one within firms. Before capitalism, he says, it tended to be the opposite: strict orders regarding the division of labor in society as a whole, but not within workplaces. Marx stresses that widespread exchange of commodities is what gives rise to the division of labor in workplaces. This highlights again why he’d begin the book discussing the nature of a commodity.

Capitalism drives much more rapid changes in a society than occurs in pre-capitalist states.

Skilled labor (tradespeople) had the power to keep capitalists from emerging while the trades also conformed to the orders from political elites in pre-capitalist societies - even though they were developing the trades that eventually helped capitalism emerge and develop.

Section 5: The Capitalistic Character of Manufacture

Breaking tasks down into simple ones (division of labor) drives the capitalist to want more workers, but more workers consume more raw materials and tools. The more the productivity of workers increases, the faster the rate at which they consume raw material and tools. Hence Marx says the capitalist is always driven to expand the variable and constant capital he has. Increased deskilling and dependence of workers ensues

Marx takes perhaps an even overly mild swipe at Adam Smith below, perhaps because much worse people like Gamier were around.

For preventing the complete deterioration of the great mass of the people by division of labour, A. Smith recommends education of the people by the State, but prudently, and in homeopathic doses. G. Gamier, his French translator and commentator…quite as naturally opposes him on this point. Education of the masses, he urges, violates the first law of the division of labour,..

Marx notes that “Some crippling of body and mind is inseparable even from division of labour in society as a whole.” He says that for centuries, starting in the 1500s capitalists failed to really exert their desired level of control over workers despite the development of division of labor, but the workshops for tools eventually gave birth to machines that made capitalists so much more powerful.

Chapter 15: Machinery and Modern Industry

This is the longest chapter in the book.

Section 1 : The Development of Machinery

Machinery greatly increases worker productivity but does not make their work day lighter because that isn’t why the capitalist invests in it. Machinery is meant to increase the portion of the workday the worker spends creating surplus value. What we call machines are just complex tools. Engineers and scientists call the simplest tools machines. He reviews some of the history of machines.

Efforts to get workers to run multiple machines were flops, but efforts to make machines replace multiple workers were immediately successful. He stresses the importance of the most basic of machines - tools - to the industrial revolution. The steam engine by itself could not revolutionize production until it became the driving force for machines, rather than human muscle.

As machines developed, industrial needs began to drive scientific research - such as studies into the laws of friction: as he put it “the conscious application of science, instead of rule of thumb”. The use of water (from rivers and streams) as a power source for machines had grave limitations: “could not be increased at will, it failed at certain seasons of the year, and, above all, it was essentially local.”. The steam engine got around those limitations.

He describes massive increases in productivity in the making of envelopes thanks to machines: “One single envelope machine now performs all these operations at once, and makes more than 3,000 envelopes in an hour.” However, he argues that automation was held back because the skilled artisans required to make the machines were not being produced as quickly as capitalists desired. The automation of machine making itself had to develop to overcome that problem. The invention of the lathe was crucial to that, says Marx. It reduced the dependence on skilled artisans to make the parts that make up machines.

Section 2: The Value Transferred by Machinery to the Product

He says that basic scientific discoveries become like “free” goods provided by nature.

He reminds us that machines are constant capital and do not create new exchange value. This refers to his earlier theorizing about tools degrading in value during production and in that way transferring value to the product. More valuable machines transfer more value than simpler cheaper ones as they degrade through wear and tear. On the other hand, he says wear and tear can become so minimal for largest and most resilient machines that they can be seen to approximate a “free” force of nature in the production process - even if one includes the cost of coal and coal required to run them.

ASIDE I have doubts about how often it would ever be the case: that wear and tear, as well as the costs to power and maintain a machine, were so negligible.

He says that to the extent the machines are made by machines they contain less labour time that comes from skilled artisans. Therefore such machines transfer less value to the product as they wear down.

To understand a comparison he makes between commodities produced by handicrafts and those produce by machines, recall his equation C’ = c + v + s

The “value due to the instruments of production” would be part of “c”. The other part of c would be raw materials. He says that generally the “value due to instruments of production” would be lower for items produced through a very mechanized process compared to a handicraft one, but it would be a larger share of C’. Why? Presumably because of a much reduced “v” thanks to automation.

He gives the following example: a machine costs £3000 and replaces 150 workers. Suppose the wages of 150 workers for one year is also £3000 . But if s/v = 100% that means the total exchange value produced by 150 workers is £6000. Marx gives the example to caution readers not to think the capitalist has merely broken even by comparing the wages of the workers displaced to the total cost of a machine. In LTV terms, the total labor time represented by the cost of the machine already contains labour time spent creating surplus value while it was built. But wages for workers on the job today do not include surplus value.

Prices and wages only approximate exchange values which Marx considers in labour hours. He remarks that the most sickening exploitation in some countries destroys the incentive to mechanize: “The Yankees have invented a stone- breaking machine. The English do not make use of it, because the "wretch" who does this work gets paid for such a small portion of his labour”

Section 3: The Proximate Effects of Machinery on the

Workman

A. Appropriation of Supplementary Labour-Power by Capital. The Employment of Women and Children

In so far as machinery dispenses with muscular power, it becomes a means of employing labourers of slight muscular strength, and those whose bodily development is incomplete, but whose limbs are all the more supple. The labour of women and children was, therefore, the first thing sought for by capitalists who used machinery. Compulsory work for the capitalist usurped the place, not only of the children's play, but also of free labour at home within moderate limits for the support of the family.

Machinery makes the pool of workers greater by removing physical strength as a requirement, More workers available puts downward pressure on wages. Lower wages pressures more family members to work if wages fall so fast that several salaries are required to replace one - and the work is now doable by women and children.

Atrocity stories follow (as Betrand Russell called them). Russell complained that these stories needlessly incited hatred for capitalists - as if we should not hate capitalists and want them punished for imposing these conditions:

In the notorious district of Bethnal Green, a public market is held every Monday and Tuesday morning, where children of both sexes from 9 years of age upwards, hire themselves out to the silk manufacturers. …Whenever the law limits the labour of children to 6 hours in industries not before interfered with, the complaints of the manufacturers are always renewed….

As was shown by an official medical inquiry in the year 1861, the high death-rates are, apart from local causes, principally due to the employment of the mothers away from their homes, and to the neglect and maltreatment, consequent on her absence, such as, amongst others, insufficient nourishment, unsuitable food, and dosing with opiates;

Manufacturers moaned as the child deaths compelled the English parliament to introduce some “compulsory education” requirements for children, which were easily evaded: “The spirit of capitalist production stands out clearly in the ludicrous wording of the so-called education clauses in the Factory Acts…and in the tricks and dodges they put in practice for evading them.”

B. Prolongation of the Working day

Marx applies the LTV to machines that become either obsolete or cheaper to produce after they’ve been purchased and put into production: “be the machine ever so young and full of life, its value is no longer determined by the labour actually materialised in it, but by the labour-time requisite to reproduce either it or the better machine”. Therefore the capitalist urge to lengthen the work day is especially acute when the machine is new - the drive to use it before it becomes obsolete. He adds that the use of machinery also increases incentive to expand the workday because it requires no more additional investment to ensure the machine never sits idle. And since machinery is more valuable than simple tools, there is more incentive to make sure they never sit idle.

Marx says that the first capitalists to use machinery get more surplus value out of their workers through a “sort of monopoly” , but this goes away as machinery use spreads. He also notices a contradiction that some critics have accused him of not noticing. Mass unemployment strengthens the capitalists’ bargaining power but also causes a waste of labor power that could be producing surplus value. Machinery - even as it displaces workers - makes the workers who remain on the job working in tandem with the machines more valuable. So it leads capitalists to to try to squeeze more out of those workers, not less

C. Intensification of Labour

The longer people work the less intensely they are able to work. Absolute surplus value is produced by workers staying on the job longer. Relative surplus value is increased by getting them to work more efficiently or more intensely. Hence there is a trade off between the production of absolute and relative surplus value. Worker rebellions force capitalists to focus more on the reproduction of relative surplus value as the legal work day is shortened. Marx cites empirical evidence that in both machinery-light as well as michery-heavy industry capitalists respond to the shorter work day by demanding greater intensity from workers: closer supervision and increased machinery speed.

Marx mentions improved engines that could be made to run faster. He should also have mentioned maintenance work which is crucial even for a factory today. Reduced worker time means more maintenance time on the machines that improves their operation and life. He cites factory owners and politicians observing that shortening the work day led to increased work intensity. He cites a factory inspector Leonard Horner, who admitted to wrongly predicting that shortening the workday would lead to decreased production. Increased intensity more than offset the shortening of the work day.

The legal workday was reduced to 12 hours in 1832 and to 10 hours in 1847. From 1838 to 1850, the average proportional increase in English cotton and other factories was 32%, while from 1850 to 1856 it amounted to 86%. Marx cites factory inspectors reporting that intensified labor intensity was doing damage to workers. Marx then predicts that the same will be observed when the workday is reduced to less than 10 hours.

Section 4: The Factory

He says the introduction of the “relays system” (what we call shift work today) was put into place during the boss’ revolt of 1848-1850. [In section 6 of Chapter 10 Marx referred to that revolt as “a pro-slavery rebellion in miniature”.

In more advanced factories work is de-skilled to the point where workers are more like replaceable spare parts than they were in less developed manufacturing systems. He quotes a bosses organization saying workers should keep in mind what a “low species” they are, but he observes in a footnote that “the ‘master’ can sing quite another song, when he is threatened with the loss of his ‘living’ automaton.”

The abuses and conditions in factories are so horrible that Marx does not consider Fourier’s comparison of them to brothels to be inappropriate. However Marx also observes that government regulation, combined with a cleaner environment required by some modern machines, has yielded significant improvements in some factories.

Section 5: The Strife Between Workman and Machine

Marx reviews worker revolts - including those led by the infamous Luddites - against machines in Europe that began to take place in the 1600s: “It took both time and experience before the workpeople learnt to distinguish between machinery and its employment by capital”. And he notes that capital’s “employment” was indeed barbaric:

History discloses no tragedy more horrible than the gradual extinction of the English hand-loom weavers…Many of them died of starvation…, English cotton machinery produced an acute effect in India. The Governor General reported 1834-35: "The misery hardly finds a parallel in the history of commerce. The bones of the cotton-weavers are bleaching the plains of India."

He shows tables of official data revealing that between 1861 and 1868, 338 cotton factories disappeared in the UK along with over 50,000 jobs. Productive machinery on a larger scale was concentrated in the hands of a smaller number of capitalists. He quotes capitalists openly proclaiming machinery to be a powerful weapon against workers.

Section 6: The Theory of Compensation as Regards the Workpeople Displaced by Machinery

He refutes several “bourgeois political economists” who claim that “all machinery that displaces workmen, simultaneously and necessarily sets free an amount of capital adequate to employ the same identical workmen”. Marx gives this example. Suppose £6000 employs 100 workers and uses £3000 of raw materials. Therefore £3000 is wages (variable capital). In that case the ratio of variable capital / total capital = 50%. Now suppose a machine that costs £1500 replaces 50 workers. Now the variable capital is cut in half to £1500, and the constant capital is £4500 (machine plus raw materials). So the ratio variable capital / total capital = 25%. That means a total capital of £6000 can only employ half the workers if the capitalist is to stay as efficient as competitors.

Marx then considers a case where the machine cost less than the wages of 50 workers it displaces - only £1000. In that case there is a savings of £500 that could be used to employ some of the workers who were let go but not all of them at the same wages. If £1500 pays for 50 workers then £500 pays for only 16.7 workers. But Marx notes that the capitalist cannot even hire that many back because some of the £500 would have to pay for constant capital that is used by the workers.

He then addresses the argument that the workers thrown on the streets by machines will be rehired as workers making machines. Again, he notes that only a fraction of the exchange value of the machine goes towards paying workers (variable capital) as it must also have components of constant capital and surplus value. He adds that machines do not need to be replaced right away, suggesting that it could not provide as steady work.

Marx adds that unemployment in one industry can cause a fall in demand for many commodities (essentially a fall in aggregate demand) which therefore spreads unemployment throughout the economy. He stresses that he is not against machinery but against the way capital inevitably employs it

As an empirical refutation of the bourgeois economists, Marx reviews statistics from England and Wales. People employed as servants, which he calls “modern domestic slaves”, outnumber the numbers employed in textile mills, mines and metal industries: “What a splendid result of the capitalist exploitation of machinery!” he sarcastically concludes.

ASIDE: Later in this chapter Marx unveils an argument that I regard as an even more powerful refutation of bourgeois economists not only of his day but of ours:

“[the capitalist] sets himself systematically to work to form an industrial reserve force that shall be ready at a moment's notice; during one part of the year he decimates this force by the most inhuman toil, during the other part, he lets it starve for want of work…

an industrial reserve army, kept in misery in order to be always at the disposal of capital”

Section 7: Repulsion and Attraction of Workpeople by the Factory System. Crises in the Cotton Trade

He cItes statistics from England and Wales showing that expansion of machines can sometimes cause a temporary increase in employment inside factories - sometimes real but sometimes only an “annexation of connected trades”. He says that the increase is also often through the employment of women and children. But he again stresses that any expansion of industry can end up employing more workers only with the smaller ratio of variable capital (v) to total capital (c + v).

Anticipating Lenin’s thesis that capitalism is “the highest form of imperialism”, Marx remarks on capitalism ensuring unemployment, emigration, and foreign colonialism: a “new and international division of labour, a division suited to the requirements of the chief centres of modern industry”.

He says the expanding productivity of factories leads to boom and bust cycles due to overproduction. Industry growth can temporarily re-employ some people, but both overproduction (which leads to busts) and constant productivity improvements work in the opposite direction: “workpeople are thus continually both repelled and attracted”.

He ends with a splendidly concise summary of the numerous booms and busts in the English cotton industry from 1770 to 1863.

Section 8: Revolution Effected in Manufacture, Handicrafts, and Domestic Industry by Modern Industry

He explains that the factory system may struggle for a while to develop in some industries. He goes into gruesome detail about the demeaning and unhealthy conditions workers are subjected to in the sorting of rags, coal mining, and tile and brick making. Marx says the unemployment caused by machines in advanced industries causes even more shameless exploitation in primitive “domestic industries” - by which he means labour intensive industry that takes place in private houses, not factories. But he adds that you can only squeeze so much money out of inefficient domestic industries by crushing the lives of children- so mechanization eventually occurs. The introduction of some machines into “domestic industries” does not always result in a proper factory system immediately forming but that is the tendency

He reiterates that increased productivity gives rise to crises of overproduction. The use of steam power to replace human power to drive the machine is the final state of the process. Factories respond to government regulations on work conditions by looking for ways to become more productive but the primitive “domestic industries” get crushed. He ridicules manufacturers who adapted to regulations they insisted would crush them.

Section 9: The Factory Acts. Sanitary and Educational Clauses of the same.

Citing extensive physicians’ testimony to parliament, Marx notes that ”one scutching mill, at Kildinan, near Cork, there occurred between 1852 and 1856, six fatal accidents and sixty mutilations; every one of which might have been prevented by the simplest appliances, at the cost of a few shillings”. He asks “What could possibly show better the character of the capitalist mode of production, than the necessity that exists for forcing upon it, by Acts of Parliament, the simplest appliances for maintaining cleanliness and health?”

He sarcastically says that manufacturers have exposed the “monotonous and uselessly long school hours of the children of the upper and middle classes” by combining child labour with the educational requirements they’d before forced to accept.

He observes that capitalism, compared to other forms of elite rule, doesn’t sit still. Its shifting anarchic ways keep workers in a state of insecurity of various forms (damaged on the job or made redundant and unemployed). However, Marx also thought that concessions wrung from capitalists in the form of compulsory education set the stage for an eventual working class take over.

Parental authority was cited as a sacred and an excuse to exploit children, but it didn't last. Wild abuses in the ”domestic industries” antagonized the regulated factory owners. He goes into detail about regulations then sums them up as follows:

What strikes us, then, in the English legislation of 1867, is, on the one hand, the necessity imposed on the parliament of the ruling classes, of adopting in principle measures so extraordinary, and on so great a scale, against the excesses of capitalistic exploitation; and on the other hand, the hesitation, the repugnance, and the bad faith, with which it lent itself to the task of carrying those measures into practice.

He recalls that “Parliament passed the Mining Act of 1842, in which it limited itself to forbidding the employment underground in mines of children under 1 years of age and females” Other Acts followed that were made useless through a lack of inspectors.

Marx lampoons a parliamentary committee report commenting that at one point the “bourgeois is not ashamed to put this question: "Do you not think that the mine-owner also suffers loss from an explosion?"

ASIDE: With centuries of hindsight, we can say Marx underestimated how long capitalism could survive by making their concessions to the working class vastly more substantive. But we can also say his critics ignore the extent to which Marxist-inspired revolutions in Russia and China in particular light a fire under capitalists so that they’d make concessions.

Section 10: Modern Industry and Agriculture

Marx does identify the environment, not just workers, as the source of fundamental source wealth that capitalism destroys.

Please send me all about book 1 Capital

I want to read all book 1. Thanks